As with most fermentation processes, the primary ingredients are (clean) water, yeast, flavoring, and a source of sugar which is consumed by the yeast and converted into CO2, alcohol, and a number of other chemicals. With beer, the sugar source is extracted from partially germinated barley, which is toasted to arrest the germination process after the bulk of the starches have been converted to sugars.

First, after deciding on the grain bill (the types and amounts of grains to add to the brew, mostly pale 2-row and 60-crystal in this case for a simple 5.5% ABV pale ale), we grind up it up, and immerse it in hot water for a good 45 minutes in what is referred to as the mashing process.

After the mashing process completes, we collect the now sugary liquid (wort) from the mash tun, extra any residual wort by adding and collecting additional hot water (the lautering process), and adding the result to a massive pot. From here, we add cheesecloth bags full of bittering agents, hops, at set intervals so the aroma and bitterness offsets the sweetness of the wort.

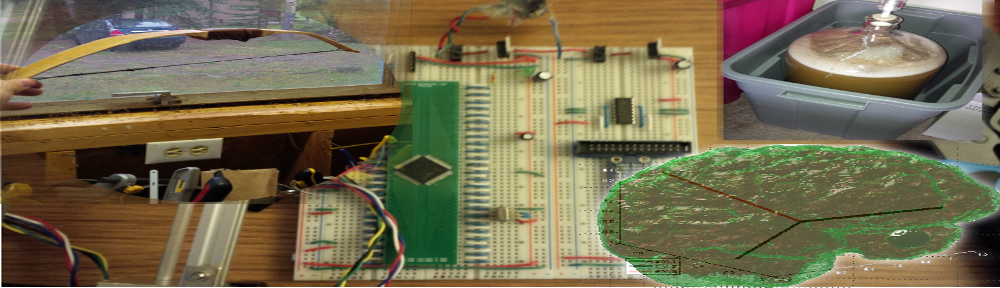

After the boiling process is complete, we rapidly cool the mixture with an immersion cooler:

Its actually quite neat to watch. The cooler is inserted into the boiling hot wort and hops mixture, which sterilizes the chiller. The ends are then connected to the tap of a sink and a runoff (ie: the drain of the sink), and cool water is run through the apparatus, acting as a heat exchanger in the massive copper coil. Once chilled, we add the yeast, and transfer the liquid to a glass carboy to serve as a fermentation vessel.

The airlock on the top allows CO2 to escape from the carboy so it doesn’t eject the rubber bung/stopper or cause the container to explode (ie: bottle bombs), but prevents outside air any potential contaminants to enter, which could cause the brew to spoil and be ruined. Three weeks later, the mixture will clear up, with all of the spent yeast and particulate matter collecting in the bottom (trub), and tasty beer at the top. We just need to bottle it, and carbonate it either via backsweetening (adding calibrated amounts of sugar to the bottles) or forced carbonation via a CO2 injection apparatus.